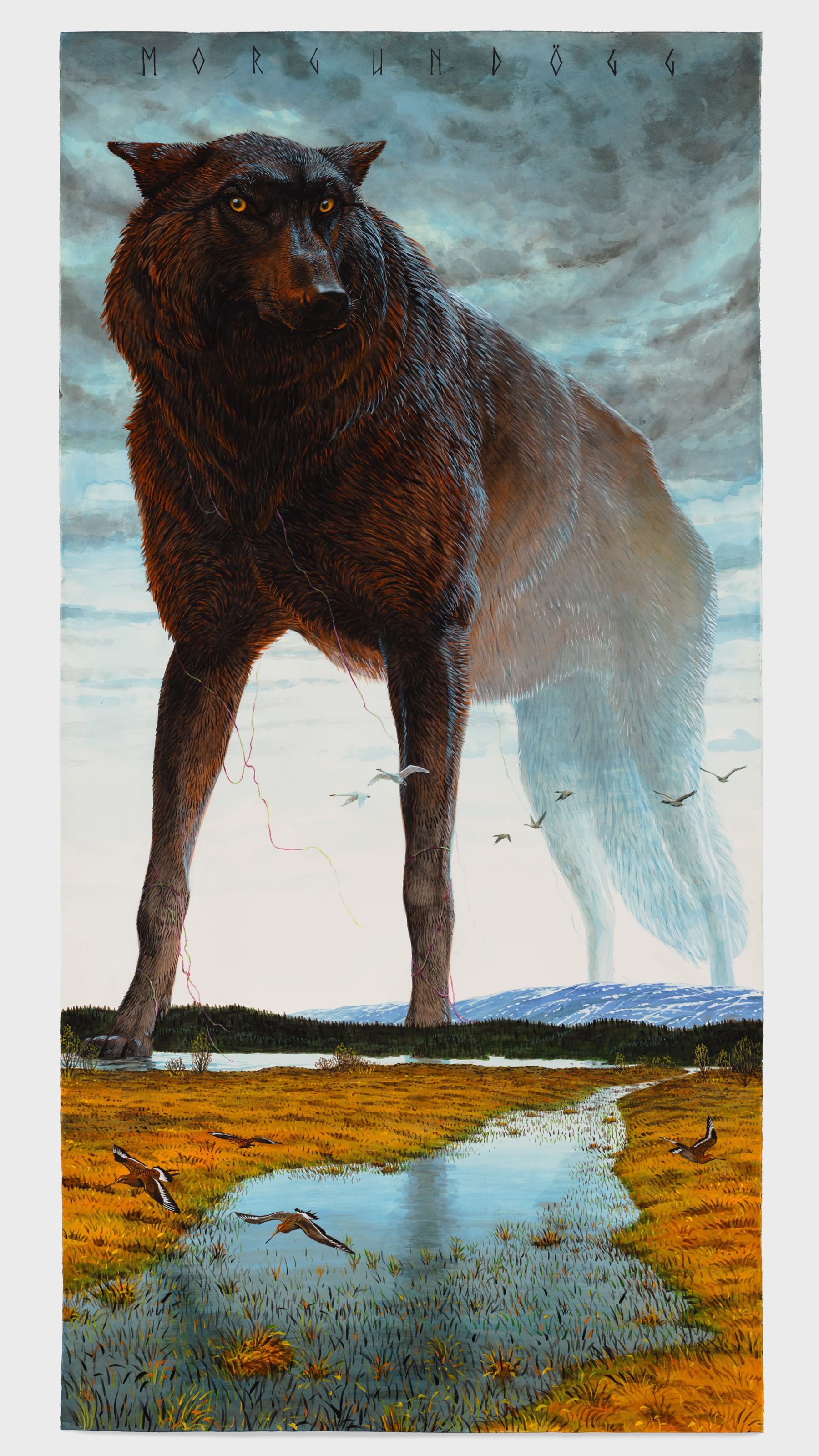

Vollmond, 2016

watercolour, gouache, and ink on paper

213.4 x 152.4 cm.; 84 x 60 in.

Photo: Christopher Burke

‘I do a lot of research, but I try to go about it in a dreamlike way. I come up with imagery that feels like it could say something new about the topic. I had a writer friend who described my project as the “imagined animal”, rather than the way they function in nature. That said, I do have various approaches once I decide I’m going to take on a subject. I get all my ideas from books and read a lot of natural history, literature, folk tales, fables, and evolutionary biology books. I get ideas for images, which often come from a hypnagogic state. I want them to have a certain resonance beyond just illustrations.’

W. Ford, ‘To Permeate a Dreamscape: Heidi Zuckerman in Conversation with Walton Ford’, in Walton Ford: Pantherausbruch, exh. cat., St. Moritz: Vito Schnabel Gallery, 2018, p. 63

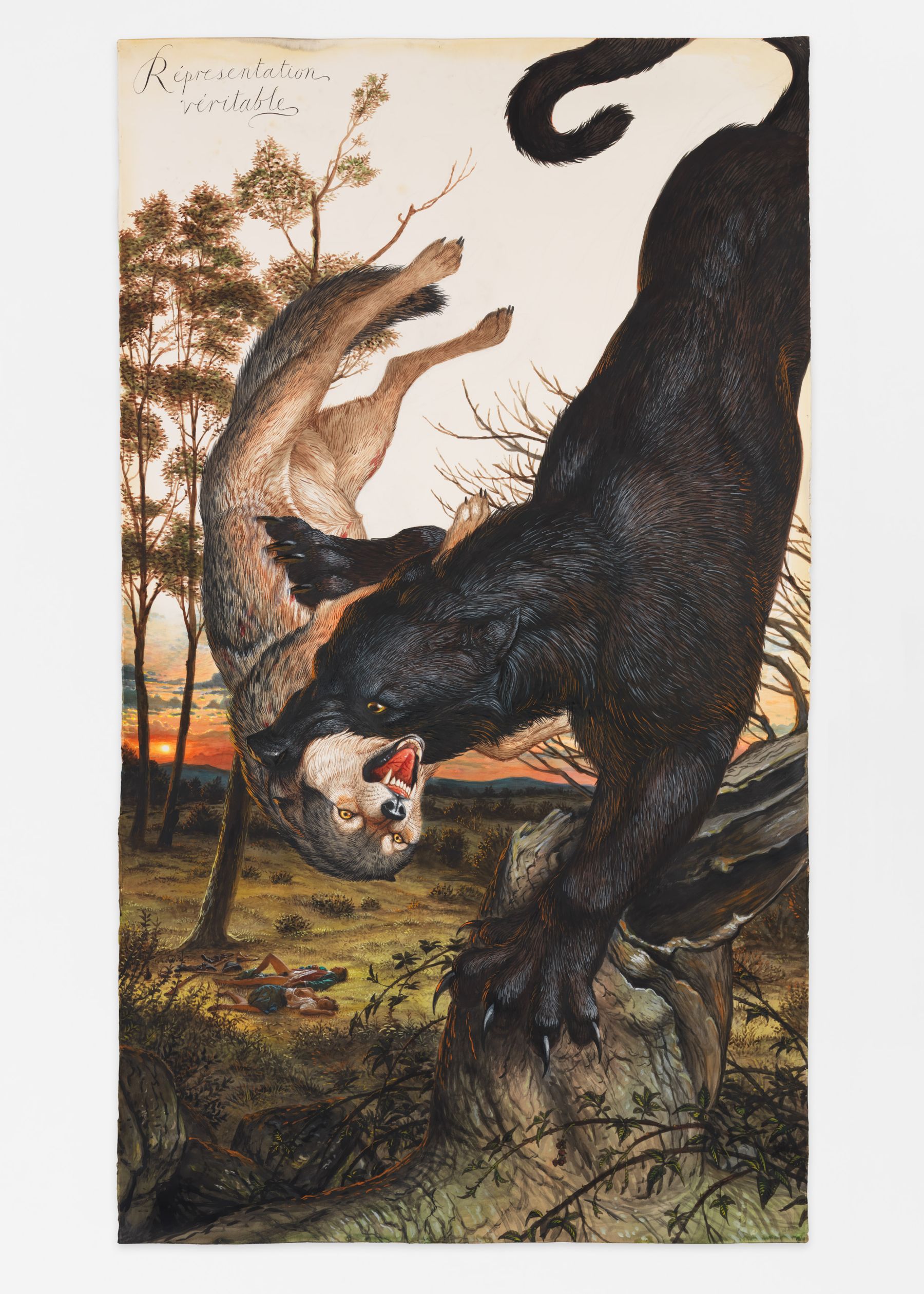

Répresentation Véritable, 2015

watercolour, gouache, and ink on paper

266.7 x 153 cm.; 105 x 60 1/4 in.

Photo: Christopher Burke

‘I remember Martin Scorsese saying that the most important thing a film director has to figure out is where to put the camera. Where is the eye? In my paintings I’m thinking very carefully about where the eye is.’

W. Ford in J. Neutres, ‘The First Things that Human Beings Painted’, in Walton Ford, exh. cat., Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris; Paris: Flammarion, 2015, p. 61

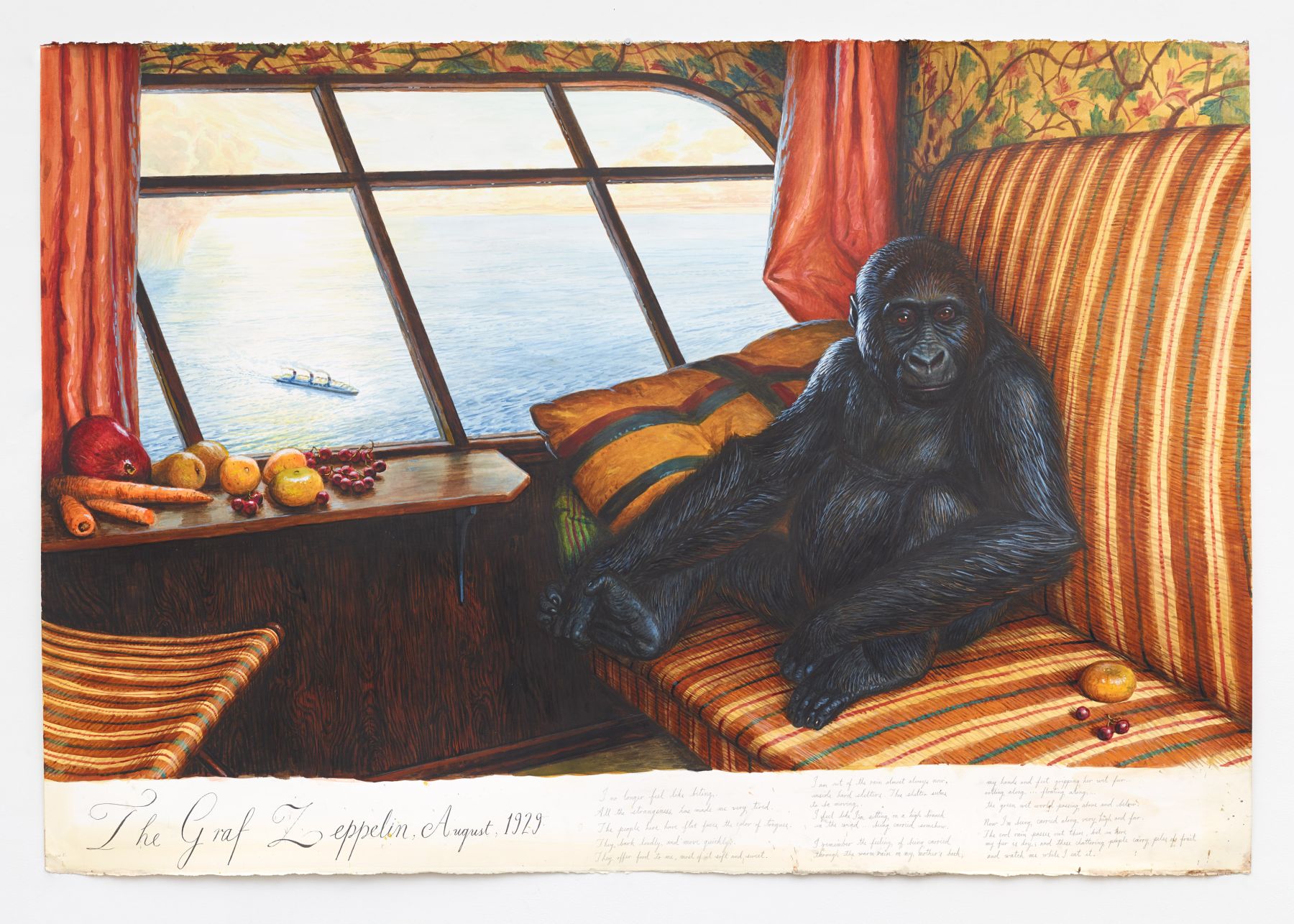

The Graf Zeppelin, 2014

watercolour, gouache, and ink on paper

104.1 x 151.8 cm.; 41 x 59 3/4 in.

Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein

‘When I read a story that gives me an idea for a picture, I try to bring elements to the painting that are not contained in the text, so there’s a visual dimension to it you could never find elsewhere. For example, I just did a painting for my last show called The Graf Zeppelin about a baby gorilla named Suzie who was brought to the United States in 1929. She rode in the first-class cabin of the Graf Zeppelin as a publicity stunt and then went on to live in the Cincinnati Zoo. There was only a sentence or two about her in this one book about zoos, but I wanted to imagine her trip and her state of mind.’

W. Ford in J. Neutres, ‘The First Things that Human Beings Painted’, in Walton Ford, exh. cat., Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris; Paris: Flammarion, 2015, p. 61

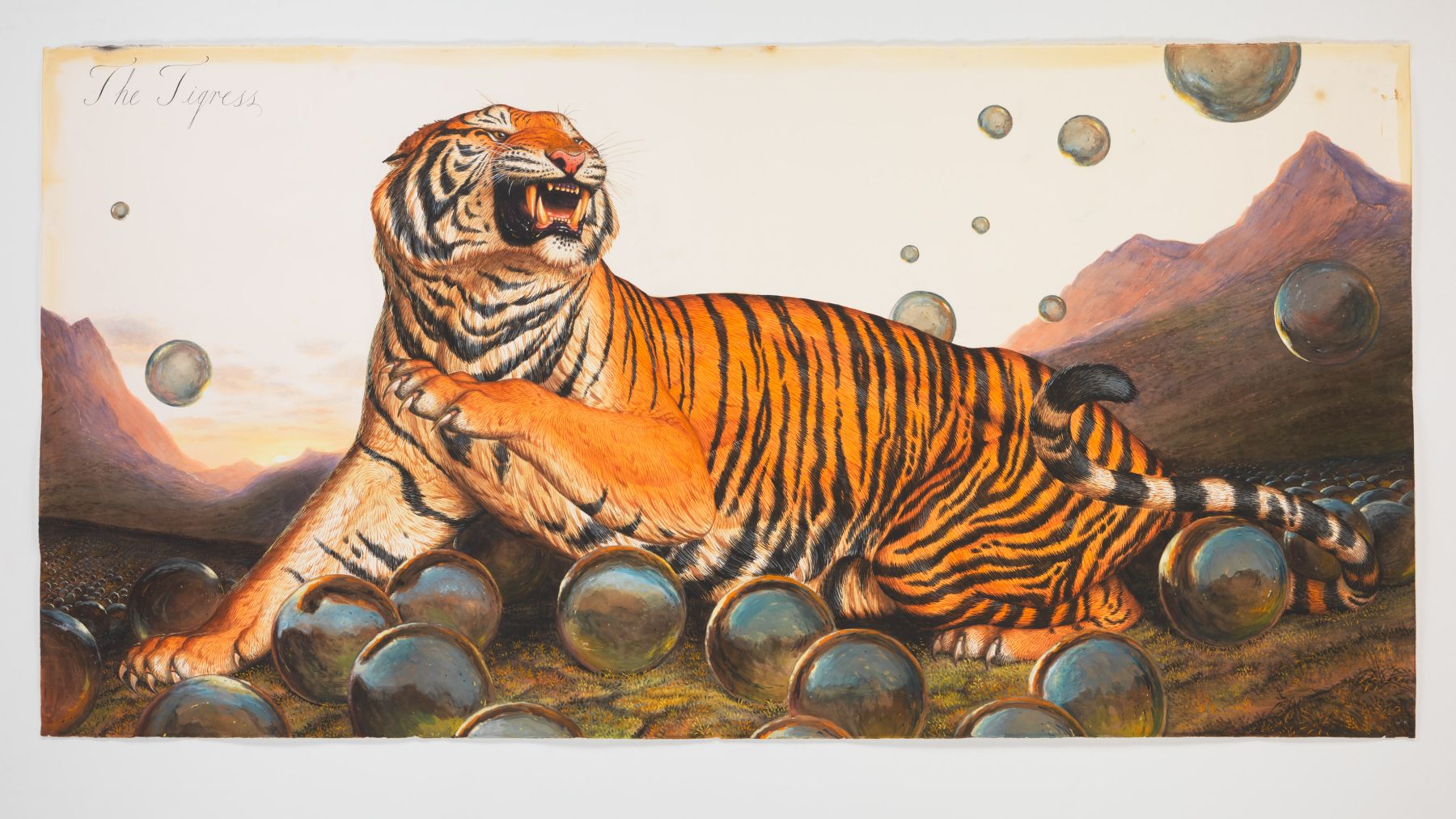

The Tigress, 2013

watercolour, gouache, and ink on paper

152.4 x 304.8 cm.; 60 x 120 in.

Photo: Christopher Burke

‘I just love certain aspects of working in watercolours. They have a unique luminosity because the pigment is suspended in a transparent medium. Optically, the paper is still reflecting light back at you through the paint like stained glass. The animal is often silhouetted against the blank paper, which becomes air and then flattens out and becomes paper again because of the notations written on it. I find this back-and-forth very beautiful and mysterious.’

W. Ford in J. Neutres, ‘The First Things that Human Beings Painted’, in Walton Ford, exh. cat., Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris; Paris: Flammarion, 2015, p. 69

Oso Dorado, 2013

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper

104.1 x 151.4 cm.; 41 x 59 5/8 in.

Collection: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by ‘One Great Night in November, 2013’ , 2014.4 © 2013 Walton Ford. Courtesy Kasmin Gallery

‘Although human beings appear only marginally in his work, if at all, most of his paintings have to do with the deep interaction between man and animal.’

C. Tomkins, ‘Man and Beast: The Narrative Art of Walton Ford’, in The New Yorker, 19 January 2009

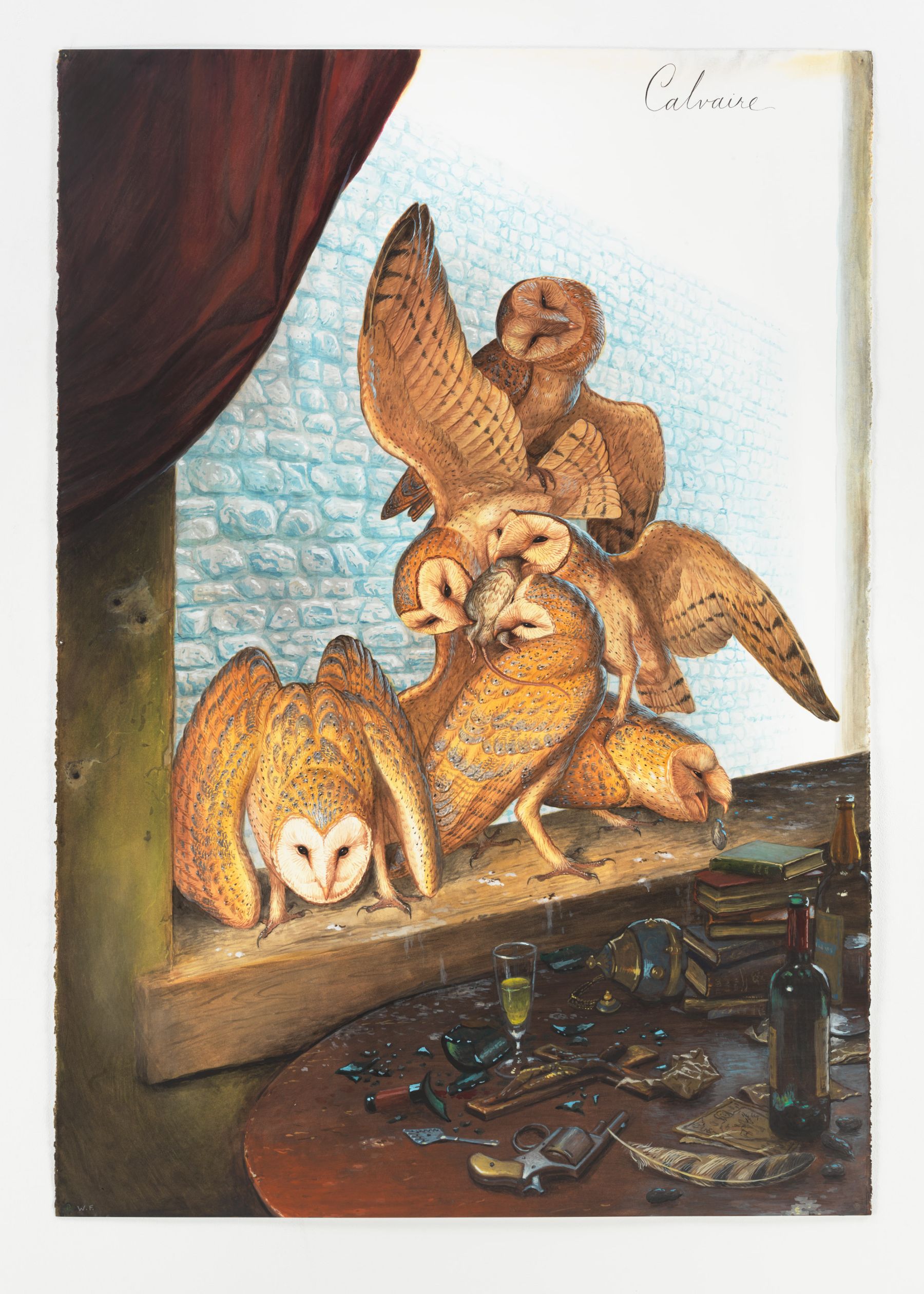

Calvarie, 2012

watercolour, gouache, and ink on paper

151.8 x 105.4 cm.; 59 3/4 x 41 1/2 in.

Photo: Christopher Burke

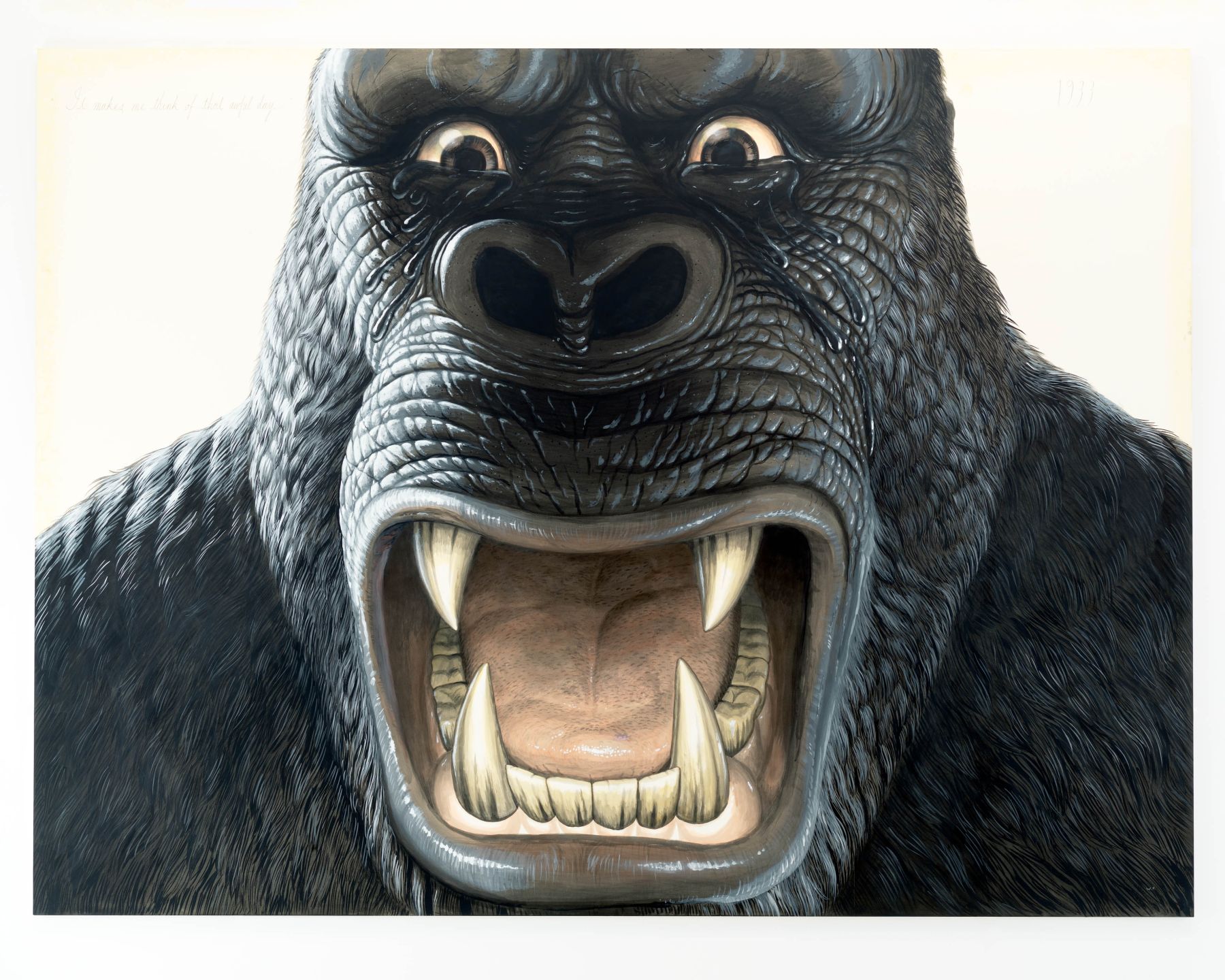

It makes me think of that awful day…, 2011

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper, mounted on aluminium panel

274.3 x 365.8 cm.; 108 x 144 in.

‘I do a huge amount of research on animals. But it’s the person that gives me a way in. Animals in the wild are boring. Before Fay Wray comes to Skull Island, King Kong isn’t doing anything. There’s no story until she shows up… What I’m doing, I think, is a sort of cultural history of the way animals live in the human imagination.’

W. Ford in C. Tomkins, ‘Man and Beast: The Narrative Art of Walton Ford’, in The New Yorker, 19 January 2009

The Island, 2009

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper, in three parts

overall: 242.6 x 345.4 cm.; 95 1/2 x 136 in.

Collection: Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, 2009.18.

‘This animal scared the hell out of the settlers. It looked like a wolf, but with stripes, like a tiger, and they could get up on their hind legs, which made them even scarier. The settlers were sheepherders, and they built up this myth of a huge bipedal, nocturnal vampire-beast that sucked the blood of sheep. The settlers put a bounty on these animals and began killing them off in every possible way – poison, traps, snares, guns. The last known one died in captivity in the nineteen-thirties, but they lived on in people’s imagination. […] My idea was to make an island out of thylacines and killed sheep – they’re not on an island; they are the island – and to have it sinking beneath the waves. I want it to be a brutal picture of thylacine bloodlust, a blame-the-victim picture, a sort of fever dream of the Tasmanian settler alone in the bush with these animals, although there was never any evidence of one killing a human being, and very little evidence of their eating sheep.’

W. Ford in C. Tomkins, ‘Man and Beast: The Narrative Art of Walton Ford’, in The New Yorker, 19 January 2009

Tur, 2007

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper, in three parts

overall: 242.6 x 345.4 cm.; 95 1/2 x 136 in.

Collection: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the American Art Forum and Nion T. McEvoy

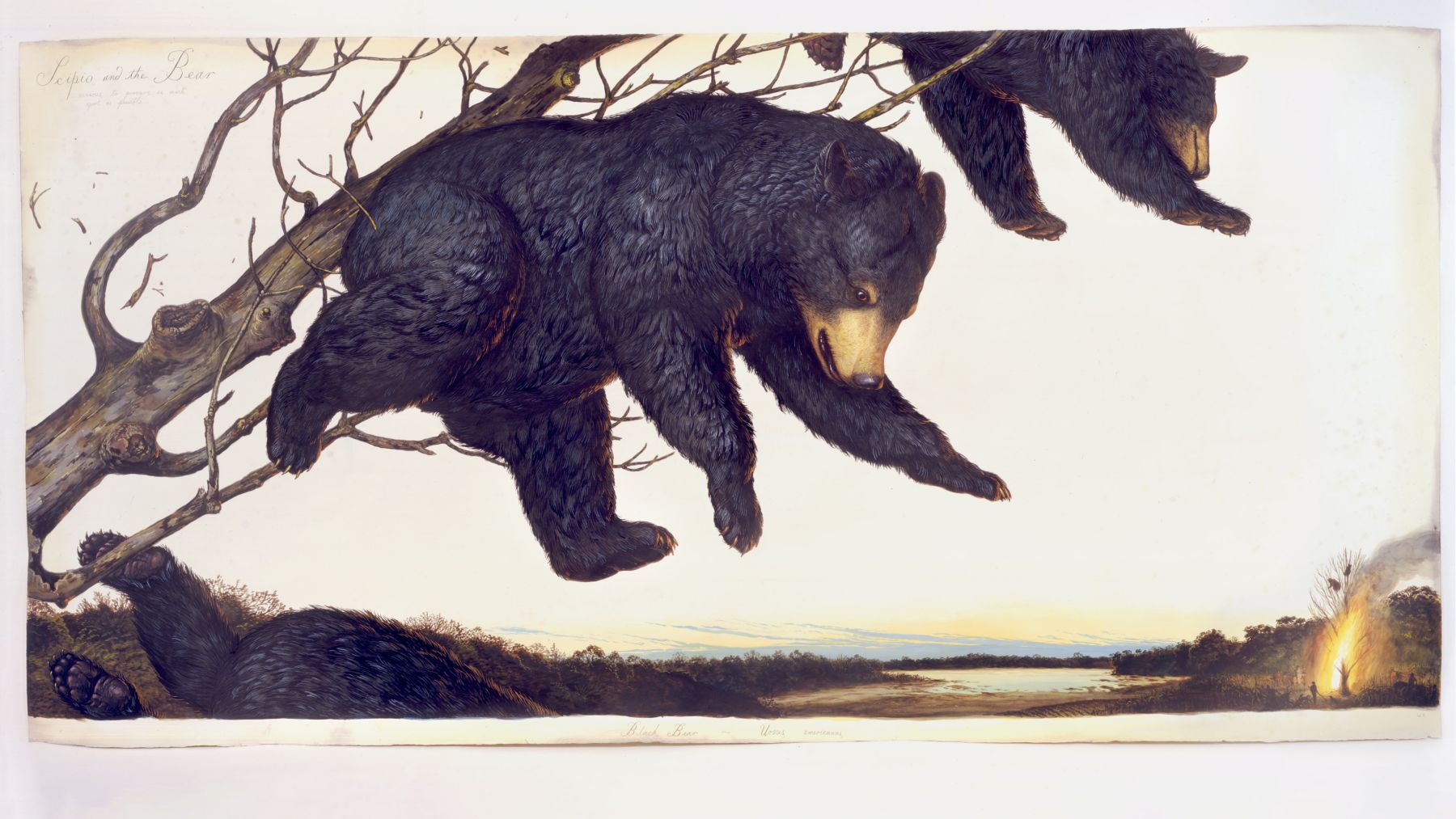

‘Ford’s watercolours ask you to see them as field notes, an anachronistic conceit, like hastily done dispatches or reports, a bearing witness (again, that explorer’s imperative) of some rare creature suddenly sighted.’

B. Buford, ‘Field Studies: Walton Ford’s Bestiary’, Pancha Tantra, Cologne: Taschen, 2007, p. 9

Scipio and the Bear, 2007

watercolour, gouache, and ink on paper

151.1 x 303.5 cm.; 59 1/2 x 119 1/2 in.

Novaya Zemlya Still Life, 2006

watercolour, gouache, ink, and graphite, on paper

framed: 163.8 x 314.3 cm.; 64 1/2 x 123 3/4 in.

unframed: 152.4 x 304.8 cm.; 60 x 120 in.

Collection: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT

The Douglas Tracy Smith and Dorothy Potter Smith Fund, 2006.12.1

Photo: Allen Phillips/Wadsworth Atheneum

‘The entry level to a Walton Ford painting is dazzling draftsmanship and sheer knock-out visual pleasure.’

D. Kazanjian, ‘A Conversation with Walton Ford by Dodie Kazanjian’, in Walton Ford: Tigers of Wrath, Horses of Instruction, New York: Harry N. Abrahams, 2002, p. 64

The Sensorium, 2003

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper

152.9 x 302.3 cm.; 60 x 119 in.

‘The original impulse is to make a nasty little underground cartoon on a really large scale. I had a lot of fun making these vignettes. They’re satisfying all their lusts and all their cravings and all their crazy desires, as they’re going down. And to me there’s a sort of black humor to that.’

W. Ford in ‘Humor’, Art in the Twenty-First Century, Season 2, 1 October 2003, 46:50

Eothen, 2001

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper

101.6 x 152.4 cm.; 40 x 60 in.

‘There’s a memoir called Eothen by Alexander Kinglake, about his travels in the Holy Land. It’s one of the most enjoyable works of travel literature. Anyway, it’s an image of a peacock in a desert landscape with mountains in the background. The peacock is following a viper, which is slithering along in front of it. The peacock’s tale has been burnt off and it’s smouldering as he drags it along. There are starlings, my Western interlopers, all over the peacock’s back, watching the proceedings. It’s a weird little introspective moment. The image just popped into my head and it seemed exactly right.’

W. Ford, ‘A Conversation with Walton Ford by Dodie Kazanjian’, in Walton Ford: Tigers of Wrath, Horses of Instruction, New York: Harry N. Abrahams, 2002, p. 63

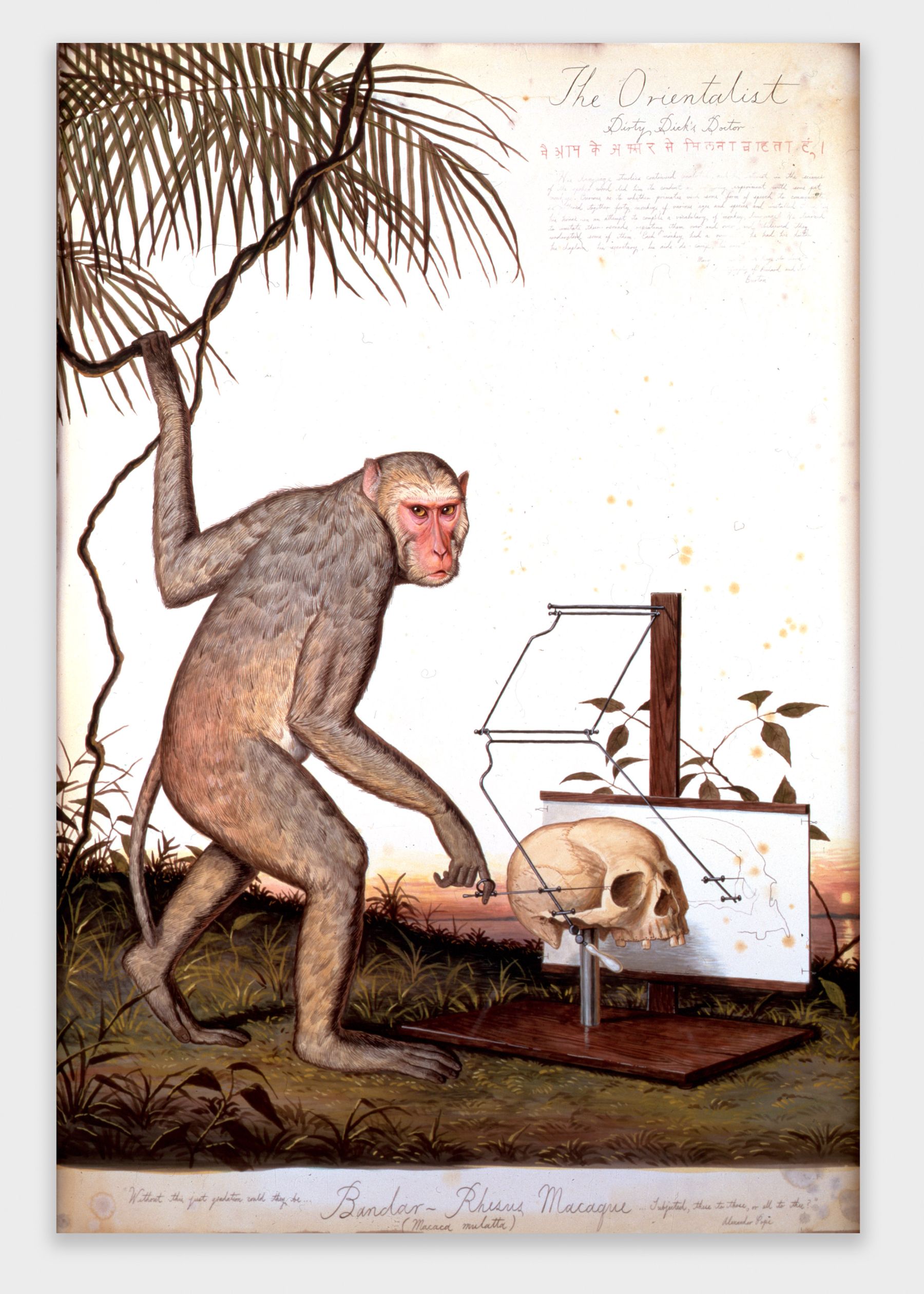

The Orientalist, 1999

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper

152.4 x 101.6 cm.; 60 x 40 in.

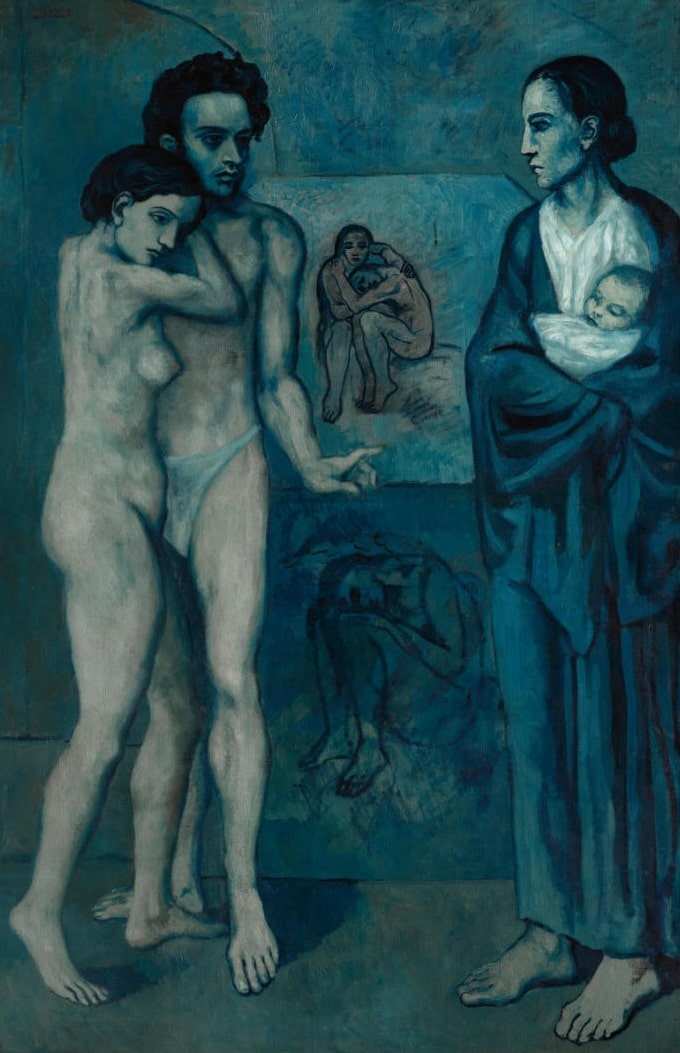

‘Taken together, Ford’s paintings constitute a bestiary with Surrealist overtones. At first sight, his monumental watercolours could read as enlargements of animal illustrations. But we soon realize that things are not what they seem. Ford’s creatures have neither the expressions nor the postures found in the old treatises of natural history. Never domesticated, but too intelligent to be only wild, these unclassifiable animals belong to a third genre. Which, in a way, is what Ford aspires to do: as a contemporary artist unlike others, going against the current of the conceptual doxa, developing a kind of ‘pulp art’ which combines in novel ways classical references and the codes of mass culture. But then, is that not the artist’s very condition: to be a kind of wild animal who refuses to be domesticated and lives off the beaten track, creating his own world?’

C. d’Anthenaise, ‘Animals of the Mind’, in Walton Ford, exh. cat., Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris; Paris: Flammarion, 2015, p. 88

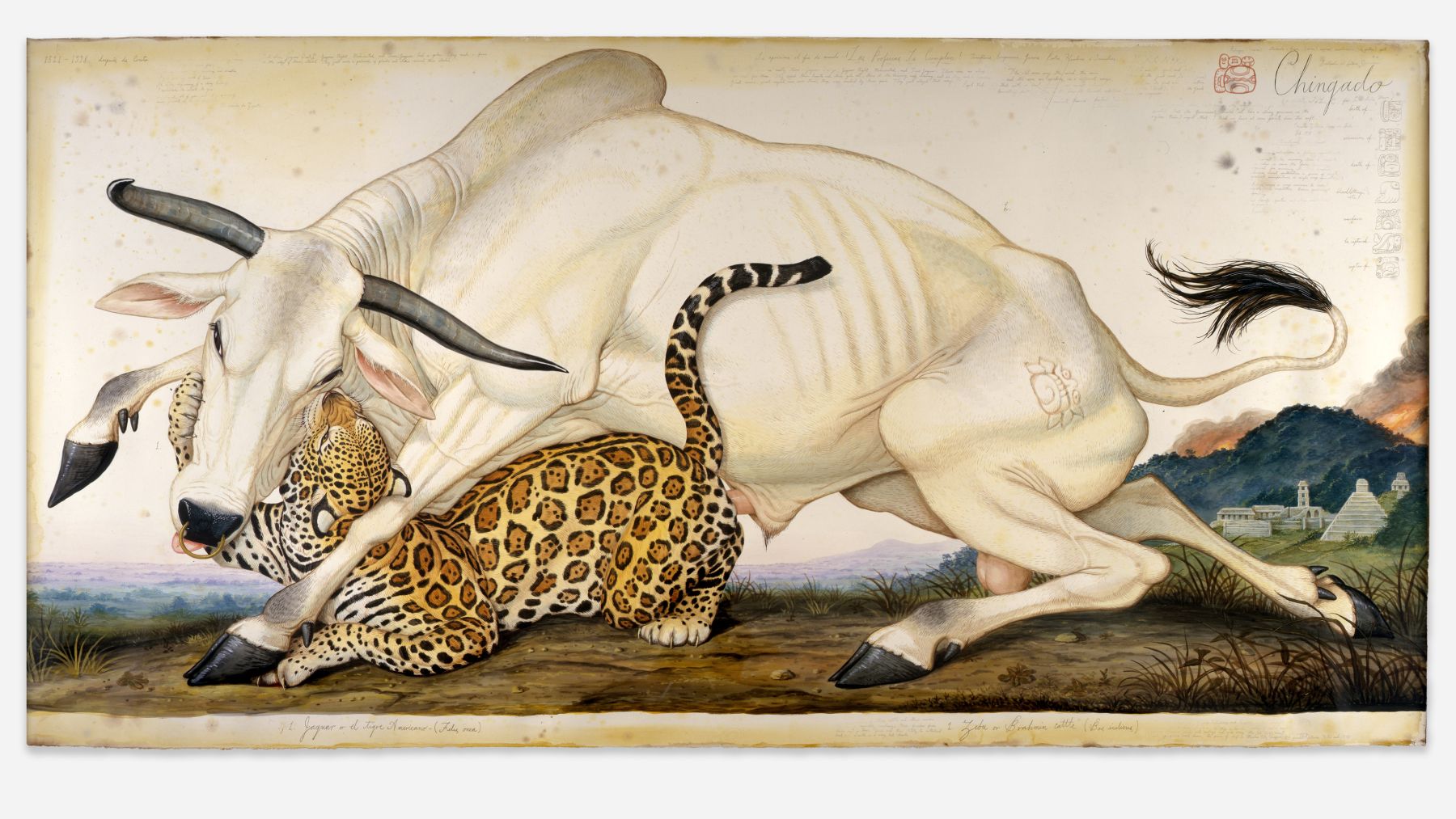

Chingado, 1998

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper

152.4 x 302.3 cm.; 60 x 119 in.

‘Each contains a narrative or narratives within narratives, with social and political messages that usually have to do with the baleful effects of Western domination over nature or older Third World cultures.’

D. Kazanjian, ‘A Conversation with Walton Ford by Dodie Kazanjian’, in Walton Ford: Tigers of Wrath, Horses of Instruction, New York: Harry N. Abrahams, 2002, p. 62

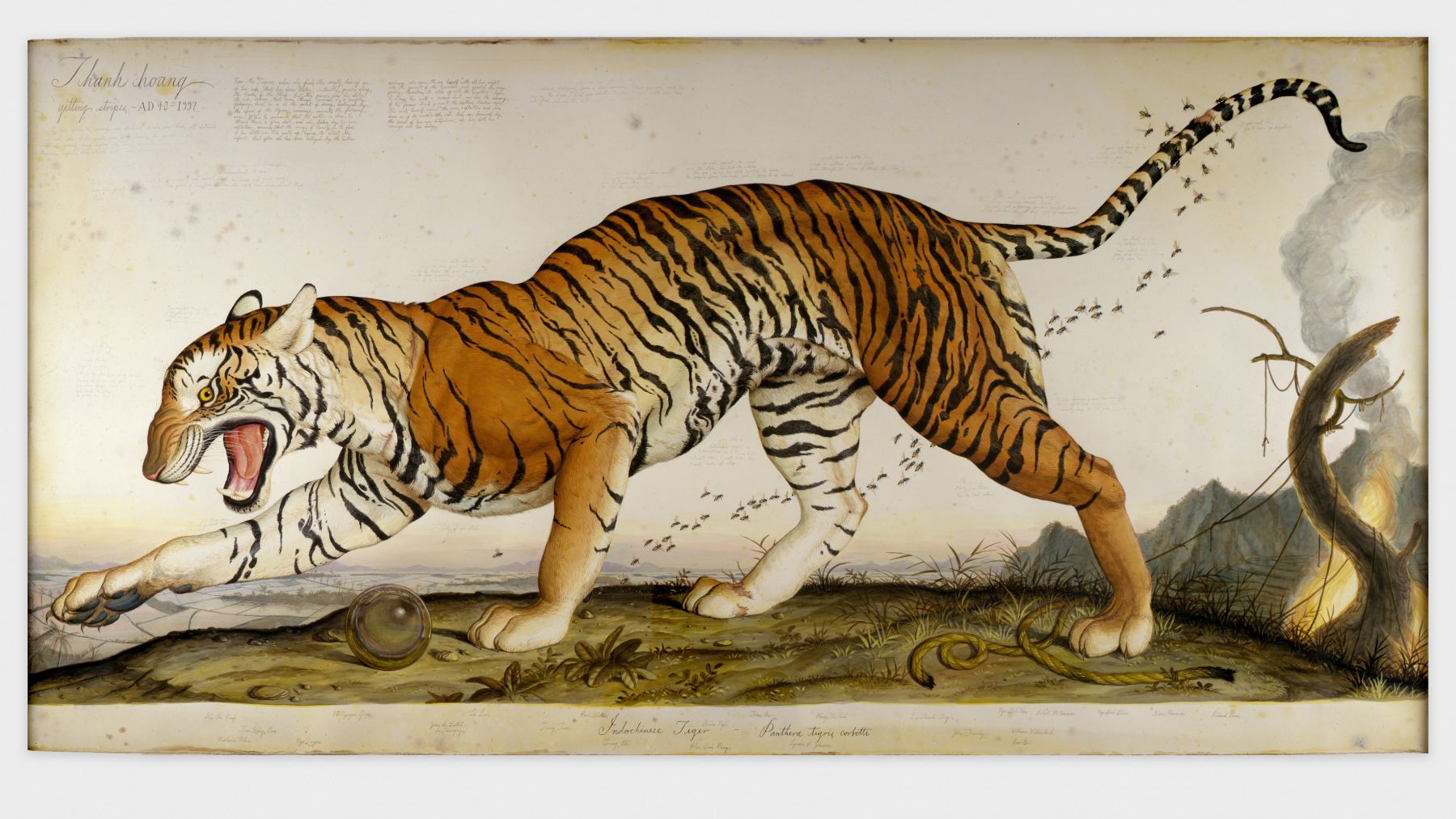

Thanh Hoang, 1997

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper

153.7 x 303.5 cm.; 60 1/2 x 119 1/2 in.

‘I’ve been working on this project of the imagined animal, of the animal in human culture rather than the animal in nature, for the past twenty years. The animal that walks around in nature without people there doesn’t interest me, but when it comes in contact with people, suddenly there’s a story. I’m very interested in fairy tales, hunting narratives, museums of natural history, exploration, and all these different ways in which people are put in contact with wild animals that they don’t fully understand.’

W. Ford in Walton Ford, exh. cat., Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris; Paris: Flammarion, 2015 p. 59

Baba—B.G., 1997

watercolour, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper

105.1 x 74 cm.; 41 3/8 x 29 1/8 in.

‘Ford’s meticulous renderings of birds - his early works are based on North American bird species and later ones are based on birds from India - are politically charged commentaries on the current state of the environment, political and cultural affairs, and foreign policy.’

A. Ferris and K. Kline, ‘Brutal Beauty’, in Walton Ford: Brutal Beauty, exh. cat., Brunswick: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 2000, p. 3

‘Bill Gates went to India and I remember reading the Indian newspapers. They were so excited about him coming, and he practically never left his hotel. They rolled out a red carpet that he didn’t walk down. They were incredibly humiliated. So I made a painting of it called Baba - B.G. where he’s a little kingfisher. He’s got a tremendous pile of fish and he’s holding forth, and all the little kingfishers from India are trying to listen to him, getting lessons on greed. In my mind it is closely related to that Breughel print and drawing of the big fish and the little fish.’

W. Ford, ‘A Conversation with Walton Ford by Dodie Kazanjian’, in Walton Ford: Tigers of Wrath, Horses of Instruction, New York: Harry N. Abrahams, 2002, p. 67

All images except Ausbruch, Eureka, La Brea and Grifo de California: Courtesy of Walton Ford and Kasmin Gallery

Eureka, La Brea and Grifo de California: Courtesy of Walton Ford and Gagosian Gallery

Ausbruch: Courtesy of Walton Ford and Vito Schnabel